Gallery

‘Our planet is still full of wonders. It’s not just the future of the whale that today lies in our hands: it’s the survival of the natural world in all parts of the living planet. We can now destroy or cherish. The choice is ours.’

Sir David Attenborough

Hadza hunter gatherer tribe, northern Tanzania

The hunter-gatherer Hadza people are thought to have lived in Yaeda Chini, in Tanzania's Central Rift valley, for up to 100,000 years. The men hunt with bows and arrows; the woman gather roots and tubers. Wild honey is collected from baobab trees. Over the past 50 years, however, the Hadza has lost 90% of its land. I spent a week with the Hadza in 2008. Photographs © Joanna Eede

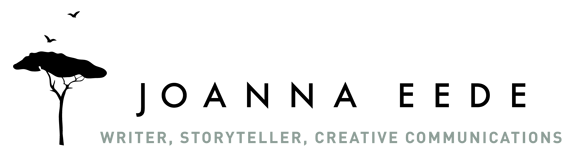

Expedition with Innu Indians across Quebec and Labrador

In 2012, I snow-shoed across Quebec and Labrador for three weeks with a team of forty Innu Indians who were following ancestral migration trails. For 7,500 years the Innu were semi-nomadic; an active, strong people sustained by a diet of caribou, berries and fish and united by a love of 'Nitassinan' (the country). During the mid 20th century, however, the Innu people were pressurised into settling into fixed communities. As a people, they fell apart. Giant led the expedition to reconnect young Innu to their homelands. 'My ancestors used to walk this way,' one Elder told me. 'I can feel them here.'

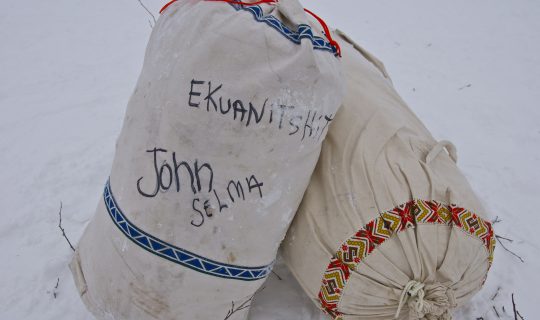

Lion collaring on Borana Conservancy, northern Kenya

Humans have shared their homelands with lions for millennia. They were still widespread across sub-Saharan Africa at the time of the first western settlers. But in 1975, estimates given by the IUCN put wild numbers at approximately 200,000 and today, it is thought there may be no more than 20,000 wild lions left; the general consensus among experts is that numbers of wild lions are in ‘free-fall’. Several ranches in Kenya's Laikipia region recently began to explore ways in which wildlife and ranching could coexist: Borana Conservancy was at the forefront of this change. ‘Commercial ranches in Laikipia are now acting like national parks in terms of providing lion sanctuary. They are hugely important for lion numbers,’ said Michael Dyer, Borana’s owner. I spent time working on Borana with leading conservation biologist Dr. Alayne Cotterill as she and a wildlife team collared a lioness. ‘If lions don’t wear collars, we don’t know where they are,’ Alayne told me as we bumped across Borana’s basalt hills. Collars can help to keep lions alive.’

Black rhino tracking in Kenya

Dark clouds are building over the Laikipia plateau, the light is fading and a sickle moon is low in the sky when the Rangers jump from the Landcruiser and crouch in formation in a sea of silver grass, one facing due north, the other south. They then walk soundlessly into a stand of trees at the top of the hill, from where they will have a vantage point over Borana’s highlands and the acacia groves of Ngare Ndare river, to Lewa’s vast volcanic plains.

The black rhinoceros has roamed the earth for five million years, yet it is now facing the greatest threat in its history, from poaching. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the animal is “teetering on the brink of extinction.” There are just over 5,000 left in the wild in Africa.

However Lewa-Borana's Black rhino conservation programme has been so successful that its 93,000 acre ecosystem is now home to 13% of Kenya’s Black rhino. While the success of the sanctuaries has led to an increase in the rhino population, the threat to Black rhino is still huge - ‘I can’t tell you how massive it is,’ - says Ian Craig - and the 24/7 task of keeping Black rhino alive a complex and expensive one. Rhino protection requires a fleet of Piper Super Cub ‘planes and helicopters, a core team of armed anti-poaching rangers and unarmed scouts, as well as fence maintenance personnel, radio operators, field vets, mechanics and office staff.

Every ranger is put through months of SAS-training in navigation skills, first-aid, aviation and evacuation training and night tactics (100% of rhino are killed after dark). Some are taught to handle bloodhounds and Belgian Malinois attack dogs, while all have Kenya Police Reservist status, which awards them the powers to arrest and prosecute.

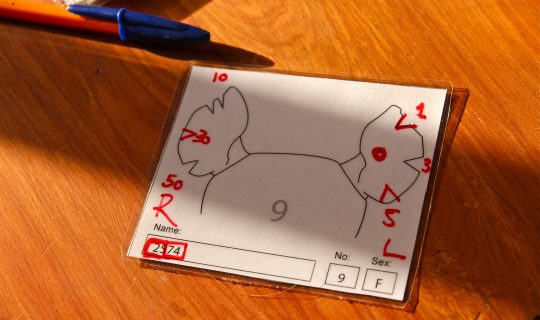

Born Free

Will Travers, President of the Born Free Foundation, was only five years old when his parents, actors Bill Travers and Virginia McKenna, stayed in an old settlers house at the foot of Mount Kenya while filming the classic wildlife film, Born Free. But Will and his siblings were not allowed anywhere near the set, he explains we fly in a Twin Otter plane from Nairobi to Meru National Park, in northern Kenya. “Kids and lions don’t mix,” he says. “The behavior of children is just too volatile. We could have triggered unwanted responses in the lions.” So the Travers children spent ten months studying safari ants and learning how to ride horses (and the occasional Boran cow). “I remember the huge snakes in the loos,” he says. “And I spent hours sitting under a fig tree, fishing in the river.”

Meru National Park has been associated with lions since game warden George Adamson and his artist wife Joy raised Elsa, an orphaned lioness cub to adulthood, and successfully released her back into the wild. Joy wrote about their intense love for Elsa in the book, “Born Free”, which was made into an Oscar-winning film in 1966. To mark the 50th anniversary of the film, Will and I are en route to Meru to observe vital new lion conservation projects.

On foot in the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco

It had taken the camels and their black-turbaned Berber herders four long days to walk from the Sahara. When we met them, the dromedaries’ panniers were being loaded with everything we needed for a three-day hike in Morocco’s High Atlas mountains: blankets, wicker stools, water drums and—bliss—an endless supply of Moroccan pastries.

Our guide, Mouha, glanced up at the trail that disappeared far into the ochre uplands. 'Time to start walking,' he said. 'Yella! Let’s go!'

The sun was lowering over the peak of Jebel M’goun and a two-hour hike still lay between our camp, a lamb tagine, and us. So, I followed this fleet of the desert along an old mule path, out of the Valley of Ikamdoulen and up into the M’goun massif.